Leaders in business education increasingly acknowledge that, as Andy Hoffman put it in his Harvard Business Review article entitled Business Education is Broken, “newly minted MBAs…graduate ill-equipped to face the challenges of management in a world where business must be an integral player in solving humanity’s biggest problems.” Equipping students for that world means going beyond traditional offerings in corporate finance, strategy, and marketing to provide the “tools, knowledge, and, importantly, judgment and wisdom to run successful businesses and create value for society.”

Among the list of six skills every MBA graduate needs exposure to, according to Hoffman? Systems thinking. “If students are to understand and address 21st century problems, they must be taught to think in systems,” he continues.

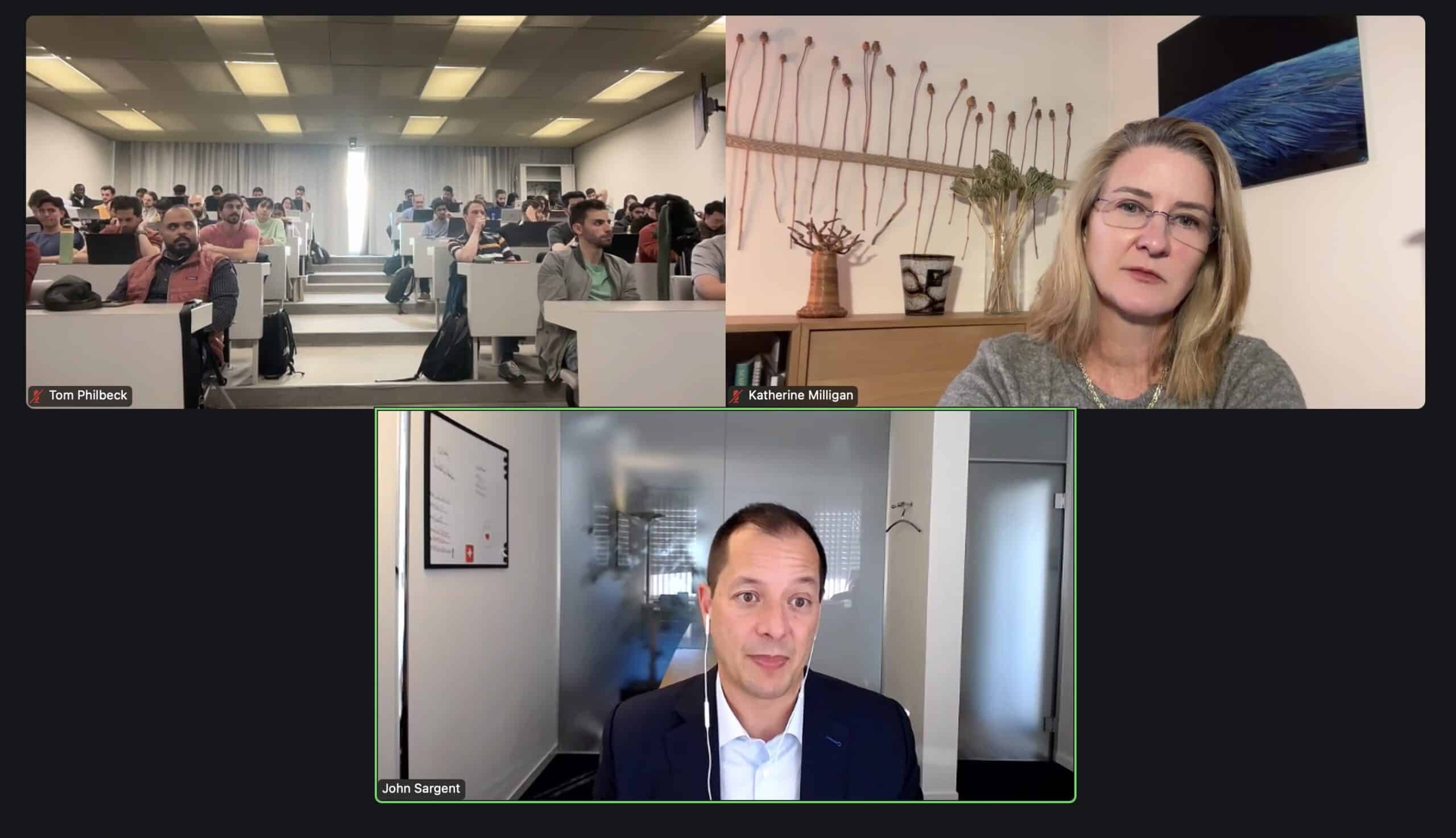

Top-ranked business school HEC-Paris is already experimenting with new courses that embed a systems lens to business transformation, helping students apply these concepts in action. Professor Tom Philbeck, Managing Director of SWIFT Partners, offered a course for the first time in fall 2024 entitled “Leading with AI: Generating Value Through Systems Leadership” to a maxed out enrolment of 70 MBA students at HEC. During the course, students were exposed to the range of actors who have a stake in how AI is shaping the business landscape and discussed why that matters for value creation.

John Sargent, Founding Partner of BroadReach Group, a health-tech venture implementing digital transformation for large-scale health programs tackling HIV, COVID-19, tuberculosis, diabetes, and cancer in several African countries and the US, and Katherine Milligan, elea Fellow at IMD and Faculty Member of the Geneva School of Economics and Management at the University of Geneva, joined Professor Philbeck to share their real-world experience and engage HEC students around capacities needed for systems leadership.

Drawing on BroadReach’s work over two decades to improve the global public health system, here are three insights for aspiring business leaders discussed during the course:

1. Systems are relational.

We tend to think of systems in mechanistic terms (an image of interlocking cogs and wheels comes to mind), which creates the fallacy that we can fix them much like a car mechanic might add some oil, replace spark plugs, and get the car back on the road. That mechanistic paradigm is utterly unsuited for social systems, however, which behave not as complicated pieces of machinery but as complex adaptive problems.

Essentially, any social system like the “healthcare system” is an interrelated, interdependent web of existing relationships between individuals and institutions, all of whom have different degrees of power and are responding to different incentives and changing external conditions. As Katherine often tells her students: “Investigating the relationships between system actors is the surest way of figuring out what is really happening inside of a system.”

John candidly offered his own learning curve as an example. “When we first started out, I thought, ‘If we do this and change that, then the problem will be fixed,’” he said. “What I didn’t realise is that there’s a logic to how the healthcare system evolved because there are certain dynamics, deliberate inefficiencies, and longstanding relationships. If you don’t understand all of the relationships, you’re never going to get anywhere. So try to unpack it – and once you think you’ve unpacked it, you’re probably only a couple of layers in.”

Several tools such as stakeholder mapping can be useful to make the relationships and interdependencies between system actors more visible, but nothing beats doing the work of listening to multiple perspectives and building relational trust. “We’re out there talking to everyone from community healthcare workers to middle managers to hospital executives,” John continued. “And in every country where we work, we have to talk to government officials to understand their needs, work through their concerns, and craft solutions that deliver value.”

2. A system’s architecture can be make or break for your business.

Every social system is comprised not only of the relationships between people (and institutions) working in that system, but also the rules, resource flows, and roles that together comprise the “system’s architecture” and produce the current results. In the global health system, that architecture includes everything from policies set by regulatory agencies such as the World Health Organization, multilateral and bilateral aid agencies in the global north that provide a significant portion of the budgets of Health Ministries in the global south, and even entities you wouldn’t typically think of such as the African Union, which shapes laws governing digital technology and data privacy on the continent.

To grow a successful business, leaders must have a handle on who-does-what in their system’s architecture, such as who sets national regulation and who controls funding flows. Any business with operations in Africa like BroadReach that handles sensitive data such as protected health information (PHI), for example, must contend with the current reality that every Sub-Saharan African country has different rules and regulations in terms of data privacy and data residency. That leads to a lot of misunderstandings about what is possible, so BroadReach works with lawyers, Ministry officials, and others to interpret local regulations and find solutions to protect patient data.

At the same time, business leaders need to be actively involved in shaping their system’s future architecture. To continue with the same example, the African Continental Free Trade Area digital protocol is a nascent effort led by the African Union to harmonise information privacy laws across all of Africa. “Policymakers have realised all of these different national laws are a hindrance to the continent’s economic development, so we are writing articles and speaking about the proposed protocols at conferences,” said John. “And that’s just data privacy. When you start talking about AI and algorithms for clinical decision-making, that’s a whole different animal. Right now, there isn’t a lot of regulation – but that will change soon and it will have a significant impact on our business.”

3. Stay curious and humble.

What it means to be successful as a system leader is very different from the traditional markers of success in many MBA schools, such as making it on a “30 under 30” list or hitting unicorn status. “Self-promotional leadership styles and the perception of ulterior motives kill trust,” shared Katherine. “Strong self-awareness, active listening skills, and the ability to translate between public and private sector mindsets and lingo are vital skills for system leaders.”

John put it even more simply. “It’s absolutely essential to work with all of your stakeholders to understand their needs,” he shared with students. “Be curious, humble, and patient – this work is a lifelong journey.”

John Sargent is the Founding Partner of Broachreach Group.

Katherine Milligan is an elea Fellow at IMD and Faculty Member of the Institute of Management at the University of Geneva. For more on systems leadership,

read The Path to Becoming a Systems Entrepreneur.